In a last ditch effort to fight

prolonged recession, BoJ finally launched the much anticipated unlimited QE. In

short, the policy focuses on keep pumping the money until the inflation doesn’t

reach the target level of 2%. Though the decision remains well debated in

financial media, whether it would be successful or not, remains yet to be seen.

Yen, nevertheless, clearly weakened as a result of this. Perhaps one may always

argue that weakened yen is always good for an export dependent economy (like

Japan) but the transmission mechanism is not simple to comprehend. Especially

in the context of ongoing currency wars where any act of currency weakening is

quickly responded.

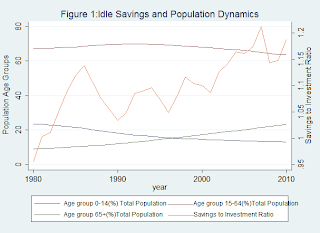

Despite above arguments, the key

to growth remains consumption. Japan’s case is also special in respect that

Japan is gradually becoming a nation of elderly. Panel 1 presents the dynamics

of population in Japan. Here the

population is distributed into three major catagories 1) Childern (0-14 Years)

Working pool (15-65 Years) and the elderly (65+ years). It is clearly visible

that the share of elderly is on the rise while the working age population is

shrinking. In addition, the share of newborns has also fallen. What seems more worrisome

is that the gap between the outflow from the working (65+ year) pool and inflow

to working pool (0-14 years) has turned negative for women much earlier than

men. This not only has implications for labor markets but also for the ability to

replenish the national labor pool. The portion of fertile women (proxies from

age distribution) has fallen significantly. If kept unchecked, sooner or later

it would start to drag the male labor pool as well.

Furthermore, in order to check

the trends in saving, I calculated the savings to investment ratio for the

country. The higher the ratio, the less the conversion of savings into

investment (i.e. more idle/unproductive) savings. Interestingly, the ratio has

been consistently rising over the time (Figure 1). This means that Japanese are

saving more but investing less. This can be proved theoretically since the

trade off between the future consumption (savings) and current consumption is

determined by interest rate (for detailed understanding of the concept please

see Prof, S K Chug’s notes here).

However, since the real interest rates are positive not because of positive

nominal interest rate (which requires investment of money) but negative

inflation (which doesn’t require investment of money) it may very well be

possible that Japanese population would be indifferent between cash savings and

not the investment. Furthermore, it can also be argued that since the average

age of Japanese population is increasing, thus it may also be possible that

lack of investment has to do something with that. Whatsoever the reason may be,

apparently Japanese are saving more and investing less.

To investigate the matter

further, I took the Japanese household expenditure data (2 or more members in

the household) from December-December basis (available here). Panel 2

represents the trends across categories of expenditure. Interestingly, trends

in most of the expenses were either stagnant or decreasing. Furthermore, I also

categorized the expenditure in inelastic (necessary expenditures) and elastic

expenditure and plotted them over time (Panel 3).Interestingly, not only

elastic expenditures but also inelastic expenditures have shown a decreasing

trend. This also indicates that Japanese are not only saving more, but also

spending less. To further investigate whether ageing had to do anything with

spending I plotted the proxy of population replenishment gap (The gap between

the 0-14 and 65+ years old population over time) and then plotted them against

both elastic as well as inelastic expenditures (Panel 4). The results turned

out to be pretty interesting. While the elastic expenditures decrease alongside

the increasing gap (which is understandable), it appears that the increasing

gap has also started to affect the fixed expenses as well. As the gap was

reducing (in positive territory), the fixed expenditures were increasing but as

soon as the gap started to turn negative (sometime around 1996-1997), the fixed

expenditures have also started to fall. This means that as more and more

population becomes aged, the deflation spiral is going to be prolonged,

something which can’t be countered by just increasing money supply.

Japan's problem is not that it lack's money. Its problem is that it lacks people who would spend that money.

Japan's problem is not that it lack's money. Its problem is that it lacks people who would spend that money.

A Note on Reproducibility:

Author considers reproducibility

as an essential tool for acceptability, improvement and propagation of

understanding. The code and data file can be downloaded from links provided

below. (Programmed in STATA)

Acknowledgements:

I owe an intellectual debt to Dr. Farooq Pasha (A good friend and my instructor in Macro-Economics) and Dr.Sanjay K Chug (For his generosity by making his lectures available on net)

I owe an intellectual debt to Dr. Farooq Pasha (A good friend and my instructor in Macro-Economics) and Dr.Sanjay K Chug (For his generosity by making his lectures available on net)

(The blog-post and code-file are the

intellectual properties of author. The material can be used for all legal and

valid purposes with proper referencing.)

Appendix: